Dreamers (1918)

Soldiers are citizens of death’s grey land,

Drawing no dividend from time’s to-morrows.

In the great hour of destiny they stand,

Each with his feuds, and jealousies, and sorrows.

Soldiers are sworn to action; they must win

Some flaming, fatal climax with their lives.

Soldiers are dreamers; when the guns begin

They think of firelit homes, clean beds and wives.

I see them in foul dug-outs, gnawed by rats,

And in the ruined trenches, lashed with rain,

Dreaming of things they did with balls and bats,

And mocked by hopeless longing to regain

Bank-holidays, and picture shows, and spats,

And going to the office in the train.

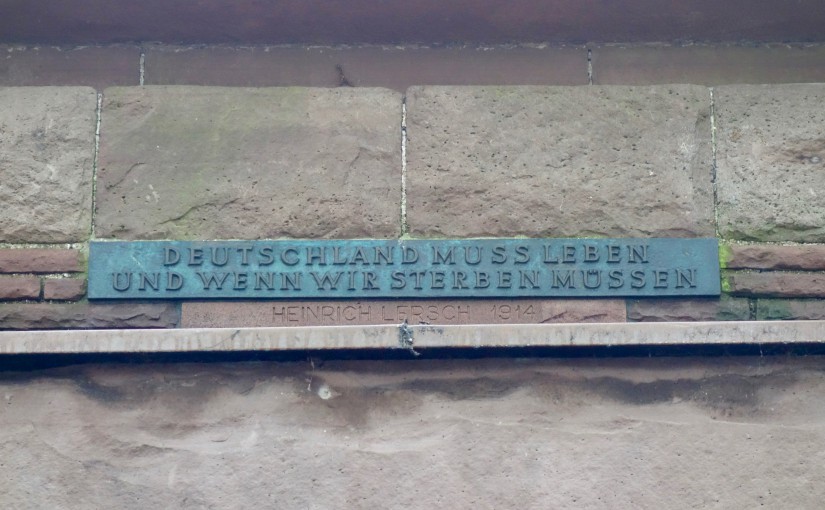

Sassoon is right, soldiers are dreamers. If they weren’t, ‘the old lie’ Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori (English: it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country; taken from an ode by Horace; see also Wilfred Owen) would not be effective propaganda. To convince people that is a wonderful, great honour to fight and die for your country you need them to be the sort that dream of being heroes, dream of a better future for themselves and their loved ones, and dream of victory.

Reinach was a dreamer too. In his letters to the Conrads there is constant mention of the future: plans for what he will teach next semester, how he will spend his vacation time away from the front, and speculation that the war will be over soon. The fact he is actively reading and writing philosophy while fighting in WWI is another sign of his dream of returning to being the academic philosophy professor; one day he’d be a retired, decorated soldier who fought in a war where Germany was victorious. Most importantly, Reinach dreamed of what phenomenology could do and be. In a letter to the Conrads dated 10 September 1915 he wrote, “I believe that phenomenology can provide that which the new Germany and the new Europe stand in need of, I believe that a great future lies open to it…” Now, he doesn’t go into further detail, all we can do is speculate what he meant and how and what phenomenology could accomplish, but what is absolutely clear is his optimism that phenomenology IS the answer.

I have spent 2017 talking about ‘Reinach the philosophical soldier’, largely because it was a year that marked the 100th anniversary of his death and battles like Passchendaele (in which he fought). I wish to spend 2018 looking more to ‘Reinach the phenomenologist’, the dreamer. This will entail exploring his phenomenology (published and unpublished works), and analyzing that fragment I quoted above to see if we can figure out what he meant and envisioned for phenomenology.

The last act in memoriam for Reinach I did in 2017, after I returned from Belgium, was to have his likeness tattooed on my leg. A memento mori, if you will, acting as a corporeal anchor fixing the memory (and here the philosophy) of the person lost. For more on memento mori, see my good friend and brilliant tattoo scholar Gemma Angel’s Blog. Over the 19 years I have studied Reinach I have spent almost as much time getting to know him personally as I have philosophically. He is more than simply a scholarly study for me; I am fond of him as a friend would be. Hence, it is only fitting to mark (figuratively and literally) the impact he has had on myself. My Reinach tattoo was done by the very talented Dustin Barnhart at Berlin Tattoo in Kitchener, Ontario. He took the few images of Reinach I had and created this wonderful old school piece. I’ll update this post later with a photo of the tattoo healed.