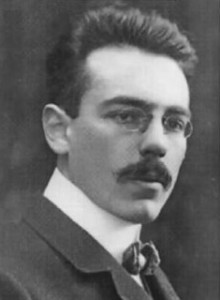

101 years ago today, Reinach took his Fronturlaub, his much deserved vacation from the Western Front of WWI. According to the Reinach-Chronik Schuhmann prepared, his vacation lasted from the 4th to the 20th of June 1915. Reinach tells Hedwig Conrad-Martius in a letter of his vacation dates and his plans to spend some of it in Göttingen.

26.05.1915

To Hedwig Conrad-Martius in Bad Wörishofen

Dear Doctor! I will get a vacation! On the 3rd, or 4th, or 5th of June! Please send your entire manuscript to Göttingen, Steinsgraben 28. Do you believe that I am glad/joyous? It is now again peaceful for us – but the situation is always changing. I am so glad that you are still in Wörishofen. I always think that the war will be over soon – don’t you? The area here is gorgeous in the spring.

Lots and lots of warm wishes, Your Reinach

The point of telling HCM was not only to share this joyous news and to begin to make plans to see her, Theodor Conrad (her husband and Reinach’s best friend), and other friends, but also to request that she send by post to his home her Jahrbuch manuscript (Zur Ontologie und Erscheinungslehre der realen Aussenwelt, 1916), so that he could read it over, comment on it, and advise her properly. One could say that during this vacation, Reinach exchanged one battlefield for another – a war of words between phenomenologists. There may have been no bloodshed, but plenty of feelings were hurt and emotions ran hot. Some vacation!

In a later letter to the Conrads dated October 9th, 1915 (the first letter written after his vacation), Reinach recounts his feelings and resolution attempts in this ‘battle’ between Husserl and Conrad-Martius:

10. 09. 1915

To Theodor and Hedwig Conrad-Martius

Dear Conrads!

That you are surprised by my silence regarding a certain point, I understand well. And also you will understand my hesitation from this letter. I was afraid that what I wanted to say would make you sad, and so I put it off again and again. But the truth of the matter is it may not actually make you sad – let alone trouble our relationship -, if we looked at this a little more closely it’s just a trivial point of differing opinions. I think your behaviour in the Jahrbuch matter was not right. I have on hand both yours and Husserl’s letters, and I have carefully read them while in Göttingen. I’ve done so with the warmest prejudice for you, I need not say more. …We all know what Husserl is like. We know his hypersensitivity, as we also know his kindheartedness, his benevolence, and his devotion to his family. We also know that his kindness and benevolence have a razor-sharp edge at the point where he gets personally hurt or with his hypersensitivity he believes himself to be hurt. We have suffered through them all, but we have known that Husserl himself suffers most and regrets it from the heart. And when there are clashes with his character, we have to willingly concede. Only in this case, it seems to me that you failed to be compliant in ways we always agreed to. Concerning the matter, he is not entirely wrong. Your manuscript was pretty difficult to read, and arguably for Husserl’s eyes it was unreadable. The length of your work was further expanded beyond the intended and arranged size. Both are certainly not bad. But Husserl – then well into an irritable mood – had taken it personally and it ever increased his testiness. Here – it seems to me, – given the gratitude and respect that we all feel for him – you should have given in; You know how easy it is to win him over with a few kind words of apology. When he sent the manuscript off to Pfänder, he meant well. He knew Pfänder knew your work and that he assessed it extremely favourably. Now Pfänder has behaved with unfriendliness and impoliteness, which is not new to me about him. This harsh manner is difficult to handle: in short, unfriendliness and condescension and impoliteness. Anyhow, it added fuel to Husserl’s sensitivity that you contacted the co-editors. He saw it as a kind of appeal to a higher authority, and he attaches the greatest importance on being the editor. So, I found him then in Göttingen very bitter and hurt. We had long discussions and I need only to assure you that I represented you in all things and I sought to settle antagonism whenever possible. The personal differences I take to be not so tragic. Husserl has had these differences with all of us – it all gets worse with this selfsame immoderateness – but nevertheless the actual consequences of this behaviour for our work concern me deeply.

By November of that same year, Reinach had successfully settled their dispute: Conrad-Martius’ manuscript was accepted for publication in Jahrbuch on the condition that Reinach would write a letter to her, the wording of which would allow Husserl to save face (beard and all). He was reluctant to write the letter – calling it an unfortunate letter – but Reinach knew it would bring peace and prosperity.

(Translation of these Reinach letters was carried out by myself and Dr. Thomas Vongehr in 2015)